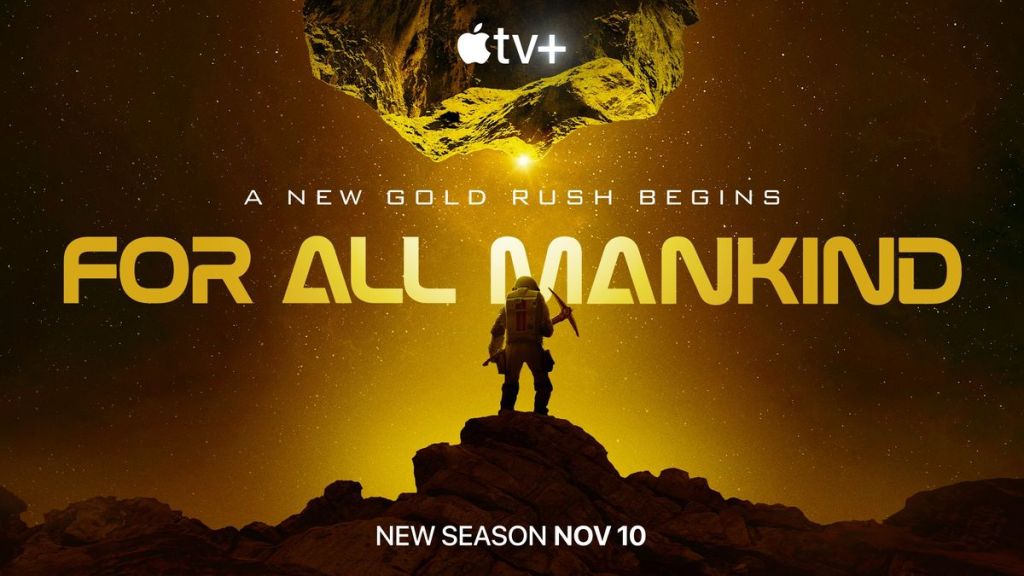

The fourth season of the alternate history TV series, For All Mankind, just concluded with a typical speculative flourish that defines the program.

Streaming on Apple TV +, For All Mankind was co-created by Ronald D. Moore and explores a reality where the Soviets reached the moon before the United States could. Instead of stagnating as in our reality, in this alternate world, the United States is inspired to keep pushing the boundaries in space exploration. In each subsequent season, the series jumps ahead roughly every decade and we see how much of an impact the Soviet moon landing has in the world. A lunar station is established in the 1970s, which further fuels the space race between the world powers of the Soviet Union and the United States. Naturally, this also fuels the Cold War which now extended into outer space as seen in season two when the two world powers nearly went to war on the moon during the 1980s.

By the third season, tensions cooled between the two powers in the 1990s. A new space race to reach Mars and the struggles of those who reached the red planet were the focus of the third season. This brings us to the fourth season which just concluded. Taking place in the early 2000s, the fourth season of For All Mankind presents a world where Al Gore is the U.S. president, the Soviet Union continues to exist, John Lennon is still alive and there are only three Star Trek TV shows (!), but as with the previous seasons, the TV show focuses on several characters affected by the alternate space race.

The heart of For All Mankind is the aging astronaut Ed Baldwin (Joel Kinnaman). In the first season, Baldwin had the opportunity to land on the moon on Apollo 10 before the Soviets, but never took it, much to his regret as Alexei Leonov landed on the moon shortly after Baldwin’s mission. Baldwin winds up involved in crititcal points in NASA’s space exploratory efforts such as being commander of the Jamestown lunar station, helping to defuse tensions with the Soviets in the second season during a space shuttle flight, and as the commander of the commercial mission to land on Mars and establish a colony there in the third and fourth season. Despite his many achievements, Baldwin struggles to find meaning in his life, to adapt to a quickly changing world and he does not even want to return to Earth after spending many years on Mars. By the fourth season, Baldwin is facing his twilight years and determined to make a difference. He does this by latching onto the quest to keep the human Martian colony from withering out.

In the fourth season, a large asteroid, called Goldilocks, is discovered drifting towards Mars that is rich in iridium. After a lot of deliberation, the M-7, a conglomeration of seven world powers, including the U.S. and the Soviets, decided to have the asteroid diverted into Earth orbit for immediate rewards and riches. Dev Ayesa (Edi Gathegi), an Elon Musk-type and owner of the corporation Helios Aerospace, has a vision of humanity expanding into the solar system and beyond. He realizes that if the Goldilocks asteroid is diverted to Earth that any interest in developing Mars and exploring space will wither and die as the world powers will be busy enriching themselves with the asteroid in Earth orbit. He comes up with a plan to essentially hijack the asteroid and have it orbit Mars instead in order to force Earth to keep investing in the red planet.

As this is going on, there is a labor struggle in the Martian colony best represented by Miles Dale (Tobey Kebbel), a former oil platform worker turned Martian laborer. In the reality of the TV show, fossil fuels have been phased out of use in the world as new energy technologies made them obsolete. While this may be great for the environment, many workers in the fossil fuel field had to find new means of employment. Dale relocated to Mars for a new opportunity, but the realities and frugality of Helios forced him to run a black market operation in the colony. Underlining these labor struggles is the fact that many of the laborers including Baldwin see Mars as their home not Earth, which means this could be the beginning of Mars eventually becoming an independent world.

Trying to keep the Martian colony running smoothly is Commander Danielle Poole (Krys Marshall), a Black woman who was one of the first woman astronauts for NASA in the 1970s. As Baldwin is the rebellious heart of For All Mankind, Poole is the soul of the show as we see from her POV how radically different this reality is from our own since women and people of color were able to advance in society much more quickly compared to our own. Like Baldwin, Poole is very relatable but for different reasons. While Baldwin is a sympathetic relic struggling to fit into the new order, Poole is an empathic and level-headed, by-the-book leader who is the moral center of the show. As these situations go, Poole is brought out of retirement to command the Martian colony and becomes embroiled in the labor struggle that morphs into a revolution of sorts on Mars.

In the backdrop of the fomenting Martian revolution, we also follow the stories of several NASA personnel. The most interesting is Margo Madison (Wrenn Schmidt), the first woman to be mission controller of NASA. During the TV show she was forced to work for the Soviets and commit treason by providing them with the secrets of American space technology. In the just-concluded season, Margo, who was believed to have been killed in a domestic terrorist bombing, comes out of hiding from the Soviet Union and has to decide what she will do with her life and how she can contribute to humanity’s space efforts. Her situation brings her into conflict with her protogee, Aleida Rosales (Coral Peña), who also is a woman of prominence in NASA.

What makes For All Mankind so captivating to watch is how it balances interesting personal stories with wider geopolical developments in this world that is distinctly different than ours. We see the impact of how a Soviet moon landing further accelerates society and technology. It’s obvious that we have the capability to have advanced in space exploration but our society lacks the drive to take us there. It’s disheartening that while there is a thriving colony on Mars in the TV show, real-life efforts show how far behind we are. We cannot even manage to return to the moon as we learned recently when the Artemis mission was delayed, yet again.

In some ways, even though we see that this is not a perfect society, it seems to be a better world than our own. Many issues have been addressed much earlier in this timeline such as the struggles of people of color , women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Advances in techonolgy are casually noted such as the use of the Internet and cell phones which began in the 1980s, and the rapid development of alternatives to fossil fuels. On the other hand, this altered world has its own problems such as it seems as if socialism/communism has spread throughout the world thanks to the continued exitence of a despotic Soviet Union (in the fourth season of the TV show, Gorbachev was overthrown by hard-line communists). One simple but intriguing tool the TV show uses is that of the montage. At the start of each season, a montage quickly brings viewers up to date on developments of the world, such as the results of presidential elections and pop culture news.

These developments would be meaningless if For All Mankind never presented how these events affected its characters. We see the wonders and struggles of this altered world through their eyes and react accordingly. One of the show’s strengths is that is able to smoothly introduce new characters while moving away from older characters as the show jumps ahead in time. It’s unknown if Baldwin and some other older characters like Poole will continue to be a part of the series though it’s unlikely. In a flashforward tease shown in the season finale, we find ourselves in 2012 without any indication if Baldwin and the others are still alive or active. With regards to the fourth season, For All Mankind continued to soar with its look at a past that is more futuristic than our own. Many episodes and plot lines were fascinating and built up to an intense and cathartic season finale.

At this time, it is unknown if For All Mankind has been renewed for a fifth season, though it is one of the more popular TV shows on Apple TV +. Not only would it be great if we’re given a fifth season taking place in the 2010s but a sixth season that takes place in this decade and beyond. Who knows, maybe we’ll see the Jovian system being colonized or perhaps of the first steps to faster-than-light travel as humanity begins to contemplate traveling to other star systems. If all goes well Ronald D. Moore and his colleagues will be able to conclude this captivating look at an alternate world of true space exploration.

José Soto